the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Assessment of risk factors for early-onset deep surgical site infection following primary total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis

Jonathan Bourget-Murray

Rohit Bansal

Alexandra Soroceanu

Sophie Piroozfar

Pam Railton

Kelly Johnston

Andrew Johnson

James Powell

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence, annual trend, and perioperative outcomes and identify risk factors of early-onset (≤90 d) deep surgical site infection (SSI) following primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) for osteoarthritis. We performed a retrospective study using prospectively collected patient-level data from January 2013 to March 2020. The diagnosis of deep SSI was based on the published Centre for Disease Control/National Healthcare Safety Network (CDC/NHSN) definition. The Mann–Kendall trend test was used to detect monotonic trends. Secondary outcomes were 90 d mortality and 90 d readmission. A total of 22 685 patients underwent primary THA for osteoarthritis. A total of 46 patients had a confirmed deep SSI within 90 d of surgery representing a cumulative incidence of 0.2 %. The annual infection rate decreased over the 7-year study period (p=0.026). Risk analysis was performed on 15 466 patients. Risk factors associated with early-onset deep SSI included a BMI > 30 kg m−2 (odds ratio (OR) 3.42 [95 % CI 1.75–7.20]; p<0.001), chronic renal disease (OR, 3.52 [95 % CI 1.17–8.59]; p=0.011), and cardiac illness (OR, 2.47 [1.30–4.69]; p=0.005), as classified by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Early-onset deep SSI was not associated with 90 d mortality (p=0.167) but was associated with an increased chance of 90 d readmission (p<0.001). This study establishes a reliable baseline infection rate for early-onset deep SSI after THA for osteoarthritis through the use of a robust methodological process. Several risk factors for early-onset deep SSI are potentially modifiable, and therefore targeted preoperative interventions of patients with these risk factors is encouraged.

Please read the corrigendum first before continuing.

-

Notice on corrigendum

The requested paper has a corresponding corrigendum published. Please read the corrigendum first before downloading the article.

-

Article

(145 KB)

-

The requested paper has a corresponding corrigendum published. Please read the corrigendum first before downloading the article.

- Article

(145 KB) - Full-text XML

- Corrigendum

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is known to be highly successful at alleviating pain and disability, providing substantial improvement in quality of life (Harris, 2009). Nationally, the number of THA procedures has increased over 20 % in the last 5 years (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021) and is projected to grow in step with the aging demographics of the population (Singh et al., 2019; Kurtz et al., 2007). As the demand continues to increase, so will the impact on healthcare costs, which are currently estimated to be over CAD 1.4 billion annually in Canada (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021). Despite improved infection prevention protocols and surgical technique, surgical site infection (SSI) and periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) following THA continue to be a serious problem. These infections result in significant individual morbidity and increase mortality risk (Gundtoft et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2015; Zmistowski et al., 2013). Due to the projected increase in demand for THA, it is highly likely that the absolute number of SSI cases will continue to increase (Kamath et al., 2015; Perfetti et al., 2017; Premkumar et al., 2021).

It is imperative to understand the most relevant risk factors associated with SSI in order to identify modifiable factors in order to improve patient care and hospital productivity and positively impact healthcare spending. Unfortunately, current large-scale studies lack comprehensiveness, which limits the generalizability of their findings and relevant outcomes. First, many do not study homogeneous groups of patients with a common primary indication for THA (i.e., osteoarthritis) but rather mixed patient groups, which does not allow for consistent comparison (Lenguerrand et al., 2018; Bozic et al., 2012). Second, variability in the definition of deep SSI can be problematic, especially when limited to patients requiring revision surgery – an indication biased by the judgment of the surgeon (Perfetti et al., 2017; Arthroplasty Collaborative Mac TM, 2020; Gundtoft et al., 2015). Doing so inherently introduces the problem of misclassification and poorly estimates the true incidence of infection. To correct this, the definition for a SSI must use validated criteria, such as those of the Centre for Disease Control/National Healthcare Safety Network (CDC/NHSN) or the Musculoskeletal Infection Society's (MSIS) (Parvizi et al., 2013; CDC/NHSN, 2021). Finally, the importance of various patient and surgical associated risk factors for SSI may vary by type of infection. For example, early-onset (≤90 d) infections account for approximately 14 %–25 % of all periprosthetic joint infections following THA (Lenguerrand et al., 2018; Manning et al., 2020). Early-onset deep SSI is of particular interest as it occurs shortly after surgery and is therefore more likely to be associated with risk factors present at the time of the surgical procedure – thus possibly modifiable (Zimmerli et al., 2004).

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence, annual trend, and perioperative outcomes of early-onset (≤90 d) deep SSI, as defined by the CDC/NHSN, following primary THA for osteoarthritis. We also wanted to identify patient and surgical risk factors specifically related to early-onset deep SSI. Secondary outcomes of interest were 90 d mortality and 90 d readmission.

2.1 Study design

This was a retrospective population-based cohort study using prospectively collected patient-level data extracted from the provincial administrative data repositories that are stored and maintained by the Alberta Bone and Joint Health Institute (ABJHI). The ABJHI is a non-for-profit organization that collates and maintains population-based provincial musculoskeletal data from all hospitals across Alberta (Canada), in a country with universal healthcare coverage. This study was approved by the local Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board and by the Provincial Health Services Research Department to allow access to patient-specific data.

2.2 Study population

The ABJHI data repositories were searched to identify all patients who underwent a primary, unilateral THA for osteoarthritis between 1 January 2013 and 1 March 2020. This was achieved using the Canadian Classification of Health Interventions (CCI) codes 1VA53LAPN and 1VA53LLPN and their variations. Patients were excluded if they had previous ipsilateral hip fracture or surgery, post-traumatic arthritis, or rheumatoid arthritis, underwent simultaneous bilateral THA, or had any admitting diagnosis other than primary osteoarthritis.

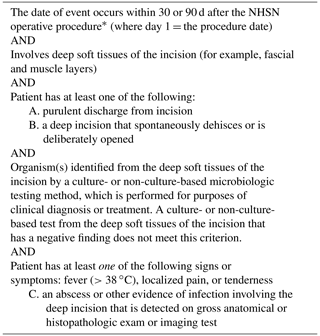

The ABJHI partners with the provincial Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) authorities for prospective surveillance and data collection of all patients admitted to any hospital facility in the province for arthroplasty (Rennert-May et al., 2016; Rusk et al., 2016). The surveillance protocol begins immediately following the surgery, continues during the acute hospital stay, and is actively performed until 90 d postoperative (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2020). IPC surveillance is conducted by infection control specialists as part of the provincial SSI surveillance program, and all patient information is entered into a centralized web-based platform. Every patient is linked to the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) and to the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System by the local analytics department. Cases of infection are detected by electronic review of microbiology laboratory results; review of patient charts, physician records, and pharmacy data; re-operation records; readmissions; emergency visit records; and clinic visit records, including observation of the surgical incision (Rennert-May et al., 2016). The diagnosis of a deep SSI is determined based on the criteria outlined by the CDC/NHSN (Table 1) (CDC/NHSN, 2021).

Table 1CDC/NHSN definition of deep surgical site infection.

The term physician for the purpose of application of the NHSN SSI criteria may be interpreted to mean a surgeon, infectious disease physician, emergency physician, other physician on the case, or physician's designee (nurse practitioner or physician's assistant). * NHSN category: HPRO. Operative procedure: hip prosthesis.

Data on patient characteristics, pre-surgical risk factors (comorbidities), blood transfusions, and acute hospital length of stay (LOS) were collected from electronic medical records, operating room information systems, the DAD, and IPC surveillance data. The ABJHI's pre-surgery risk factor methodology identifies the presence of comorbidities by screening pre-admission comorbidities in DAD and in the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Population Grouper data within 5 years prior to the arthroplasty event. CIHI Population Grouper data are extracted from provincial administrative data sources to identify the presence of 226 discrete health conditions, which are aggregated into 16 health profile categories, 13 of which were of interest for this study.

2.3 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.5 and R Studio (RStudio Team, 2020). All collected patient data were de-identified as per provincial de-identification standards and regulations. We summarize demographic data and outcomes using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were analyzed using a chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test, while a t test was used to summarize continuous variables. We evaluated trends in annual rates of deep SSI between January 2013 and December 2019. We used the Mann–Kendall trend test to detect monotonic trends in annual early-onset deep SSI rates during this timeframe. Multiple logistic regression was used to analyze the effect of different patient and surgical risk factors on the risk of developing a deep SSI within 90 d from surgery. Patient comorbidities were referenced by the ABJHI, in order to foster quality improvement. Secondary outcomes were analyzed using multiple logistic regressions. These included 90 d mortality and 90 d readmission rate, with adjustments made for sex, age at the time of surgery, body mass index (BMI), pre-surgery risk factor groups (comorbidities), blood transfusion, anesthesia type, and same-day discharge. A p value less than 0.05 was deemed significant.

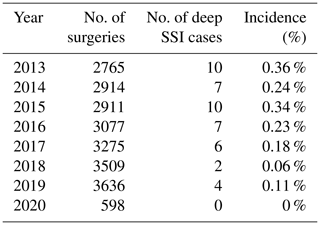

There were 22 685 patients identified who received a primary THA for osteoarthritis between 1 January 2013 and 1 March 2020. Of these, 46 patients were diagnosed with a deep SSI within 90 d from surgery (Table 2). The cumulative incidence for early-onset deep SSI during the study period was 0.2 %. The annual rate of deep SSI was found to have significantly decreased over the 7-year study period (p=0.026).

Table 2Annual number of confirmed deep surgical site infection cases within 90 d of surgery between January 2013 and March 2020.

Total no. of THA surgeries: 22 685; total no. of deep SSI cases: 46. We used the Mann–Kendall trend test to detect monotonic trends in annual early-onset deep SSI rates during this timeframe.

3.1 Risk factors for deep surgical site infection

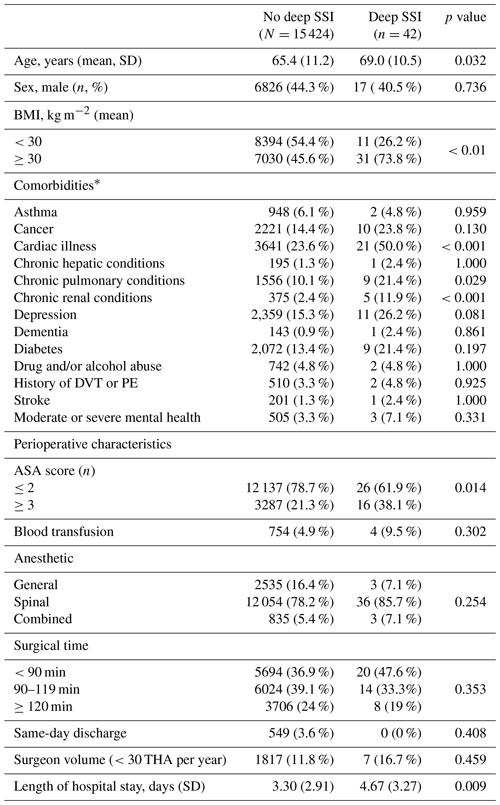

Due to some missing patient demographic and surgery characteristic data, only 15 466 patients could be included for the risk analysis, 42 of whom developed an infection. Baseline patient and surgical characteristics investigated are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3Patient demographics and surgery characteristics.

Fisher's exact test. * Comorbidities were captured using health conditions classified in the CIHI Population Risk Grouper data. “Cardiac conditions” include acute myocardial infarction or arrest, arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, cardiac valve disease, malformation of cardiovascular system, heart failure. “Chronic hepatic conditions” include chronic liver disease, including hepatic cirrhosis. “Chronic pulmonary conditions” include congenital disorder of the respiratory system, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary hypertension, respiratory failure, cystic fibrosis, tuberculosis disease, and other chronic lung disease. “Chronic renal conditions” include chronic kidney disease/failure. “Moderate or severe mental health” includes delusional disorder (inc. schizophrenia), bipolar/manic mood disorder, eating disorder, intellectual disorder/delay, and mental disorder resulting from brain injury or other illness. DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism.

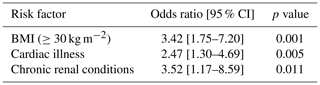

On multiple logistic regression analysis, elevated BMI > 30 kg m−2 (odds ratio (OR) 3.42 [95 % CI] 1.75 to 7.20]; p<0.001), chronic renal disease (OR, 3.52 [95 % CI 1.17 to 8.59]; p=0.011), and cardiac illness (OR, 2.47 [95 % CI 1.30 to 4.69]; p=0.005) were associated with increased risk of developing early-onset deep SSI following primary THA (Table 4).

Table 4Risk factors for early-onset deep surgical site infection.

Multiple logistic regression. Health conditions are as classified in the CIHI Population Risk Grouper data. “Cardiac conditions” include acute myocardial infarction or arrest, arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, cardiac valve disease, malformation of cardiovascular system, and heart failure. “Chronic renal conditions” include chronic kidney disease/failure.

3.2 Perioperative outcomes

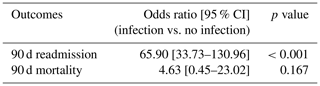

Adjusted secondary outcomes are shown in Table 5. These data were adjusted by age, sex, BMI comorbidities, blood transfusion, anesthesia type, and same-day discharge using multiple logistic regression to determine the 90 d odds ratio for readmission and mortality. Developing an infection within 90 d of surgery was associated with increased odds of requiring readmission within 90 d from surgery (OR, 65.90 [95 % CI 33.73–130.96]; p<0.001) but not associated with 90 d mortality (OR 4.63 [95 % CI 0.45–23.02]; p=0.167).

This study aimed to determine the true incidence of early-onset deep SSI following primary THA for osteoarthritis using prospectively collected population-based data extracted from our provincial administrative data repositories. The findings from this study do however only reflect data from patients with early-onset deep SSI and not those of patients who developed an acute hematogenous or chronic periprosthetic joint infection years following surgery. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, early-onset (≤90 d) SSI only accounts for approximately 14 % to 25 % of all periprosthetic joint injections (Lenguerrand et al., 2018; Manning et al., 2020). However, the aim of this study was to identify associated risk factors that are much more likely to influence outcomes at the time of the index surgery. By using data collected systematically by IPC, who perform in-depth case reviews and use validated criteria to diagnose infection (CDC/NHSN), we present outcomes and identify relevant risk factors while minimizing interobserver variability.

We identified a total of 22 685 patients who underwent a THA for primary osteoarthritis between 1 January 2013 and March 2020. A total of 46 patients had a confirmed diagnosis of a deep SSI within 90 d of surgery, representing an incidence of 0.2 %. This incidence is in keeping with other large cohort studies (Arthroplasty Collaborative Mac TM, 2020; RStudio Team, 2020; Ong et al., 2009). Lenguerrand et al. (2017) analyzed 623 253 primary hip procedures with varying admitting diagnosis and reported an incidence of early-onset deep SSI of 0.4 % (Lenguerrand et al., 2017), while Mahomed et al. (2003) analyzed United States Medicare data and reported an incidence of 0.24 % for early-deep SSI (≤90 d) (Mahomed et al., 2003). We believe our lower incidence compared to the study by Lenguerrand et al. (2017) may be explained by our study's inclusion criteria – specific to patients with primary osteoarthritis – and therefore do not include presumably higher risk populations (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis). There is only one other publication to report on deep SSI after THA for primary osteoarthritis, citing a cumulative incidence of 0.48 % at 1 year and rising to 1.44 % at 15 years, but no estimate of early-onset deep SSI (Arthroplasty Collaborative Mac TM, 2020).

Our study found that the annual rate of early-onset deep SSI following primary THA for osteoarthritis decreased between January 2013 and December 2019. This may have been secondary to ongoing changes in the arthroplasty care pathways in our province featuring central intake clinics, dedicated inpatient and operating room resources, routine use of tranexamic acid and transfusion protocols, surgical preparation and medical optimization in the form of comprehensive preoperative assessment, and mobilization on the day of surgery (Gooch et al., 2009). Of note, decolonization of patients preoperatively is not routinely performed across our province. Many of these implementations are more likely to have an immediate impact on early perioperative outcomes, including a decreased risk of developing an infection within 90 d from surgery. However, these findings oppose those from other relevant studies (Lenguerrand et al., 2017; Kurtz et al., 2012; Dale et al., 2012). An observational study using data from the United States National Inpatient Sample showed the incidence of PJI in patients having THA increased from 1.99 % to 2.18 % between 1999 and 2009 (Kurtz et al., 2012). Such findings are corroborated in the Nordic Arthroplasty Registry (0.46 % to 0.71 % between 1999 and 2009) (Dale et al., 2012). In addition, Lenguerrand et al. (2017) reviewed THAs performed in England and Wales from the National Joint Registry and showed that the prevalence of revision due to PJI in the 90 d following primary THA had risen 2.3-fold (95 % CI, 1.3 to 4.1) between 2005 and 2013 (Lenguerrand et al., 2017). Despite improvements in the arthroplasty care pathways in our province, the contrasting trend in annual prevalence between studies if likely multifactorial. However, the results in this study must be interpreted in light of the fact that any patients with any admitting diagnosis other than primary osteoarthritis were excluded. The risk of developing a SSI is known to vary according to the indication for the primary procedure. Specifically, patients operated on for primary osteoarthritis of the hip have been found to be at lower risk of being revised for PJI than those without osteoarthritis (Lenguerrand et al., 2018).

By defining cases of infection using validated criteria (CDC/NHSN), we believe the results of this study closely represent the true incidence of early-onset deep SSI in our patient population. Previous studies that defined cases of infection as those requiring a revision surgery may misrepresent the true incidence (Arthroplasty Collaborative Mac TM, 2020; Gundtoft et al., 2015; Lenguerrand et al., 2017). The reason for a revision surgery is multifactorial and at the discretion of the surgeon. Inevitably some patients are managed non-operatively with antibiotic therapy and are not captured in the data; although not a routinely acceptable treatment option, the general health of the patient must be taken into consideration. The ABJHI has created a standardized approach to improve detection and case-finding consistency which allows for improved data quality and reporting of deep SSI following total joint arthroplasty (Rennert-May et al., 2016; Rusk et al., 2016). The administrative data-triggered medical chart review with the use of IPC confirmation protocol has been shown to have a sensitivity of 90 % and specificity of 99 % (Gooch et al., 2009). This has resulted in a 1.1- to 1.7-fold increase in SSI rate compared with traditional surveillance (Rusk et al., 2016).

Several risk factors were found to be associated with the development of early-onset deep SSI: a BMI > 30 kg m−2, chronic renal disease, and cardiac illness. Interestingly, risk factors known to be important for late-onset deep SSI such as diabetes, drug and/or alcohol abuse, longer operative time, and blood transfusion were not found to be significant risk factors in this study (Arthroplasty Collaborative Mac TM, 2020; Ong et al., 2009; Kunutsor et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2018). Although only speculative, it may be that the risk factors important for early-onset deep SSI differ from those of late-onset deep SSI or that these risk factors exert different effects at different time points and that these effects may be cumulative over time. For instance, when considering the risk of diabetes on cumulative risk of PJI over time vs. no diabetes, the risk curves do not immediately diverge (Arthroplasty Collaborative Mac TM, 2020). This study may have been underpowered to detect the early effects of diabetes that might have been more obvious if we looked at later time points. In addition, it is unclear if limiting inclusion criteria to only patients with admitting diagnosis of primary osteoarthritis influenced the findings of this study.

The cause for early-onset deep SSI is likely to be multifactorial, and this study identified three potentially modifiable comorbidities. The comorbidities found to increase the risk of early-onset deep SSI following THA include an elevated BMI (≥30 kg m−2), chronic renal conditions, and cardiac illness. These comorbidities can potentially be optimized before surgery during routine preoperative counselling and physical examination. Targeted preoperative investigations should be done in conjunction with internal medicine specialists or anesthetists, and safety precautions in connection with the operation are required when appropriate.

A unique feature of this study is the homogeneous patient population who received a primary THA specifically for osteoarthritis of the hip. This is important as rates of deep SSI are known to vary according to the indication for surgery. The evidence-based, standardized criteria and rigorous methodology by which early-onset deep SSI was identified allows for a high degree of confidence in the reported incidence. Lastly, this study focused exclusively on the acute postoperative period, (≤90 d) thus identifying risk factors more likely attributable to (but certainly not limited to) the primary surgical intervention.

The limitations of our study are those inherent to large administrative databases. Inevitably, as with any database, some variables are not collected, and therefore we could only include in our analysis variables available to the ABJHI. Accordingly, the IPC surveillance in Alberta is conducted by infection control specialists, and the diagnosis of a deep SSI is determined based on the criteria outlined by the CDC/NHSN (CDC/NHSN, 2021) and not MSIS criteria (Parvizi et al., 2013). The surveillance protocol begins immediately following the surgery (as inpatients) and is actively performed for 90 d postoperative (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2020). While some authorities state that any infection within 90 d of the index arthroplasty should be considered acute (Parvizi and Gehrke, 2014), early SSI has also been defined as infections occurring within 3 to 4 weeks (Chotanaphuti et al., 2019). Therefore, the results from this study should be understood in light of this. In 2013, an IPC data quality working group began completing an additional review of provincial admission and disease administrative codes to ensure no cases of infection after total joint arthroplasty were being missed across the province (Rennert-May et al., 2016). This process allowed us, for the purpose of this study, to determine, with high accuracy, the true annual incidence of early-onset deep SSI across the province and to quantify whether the annual rate of deep SSI had changed between 2013 and 2019. Secondly, despite the large number of included patients, 7219 (31.8 %) patients were omitted from the risk analysis. These patients were excluded due to missing data or issues involving data completeness – a limitation for studies using administrative databases that is well described in the literature (Smith et al., 2018). Lastly, while the aim of this study was to identify risk factors present at the time of the index surgery, the authors acknowledge that early-onset SSI may be related to more virulent organisms which manifest at an earlier time point. In light of this, less virulent pathogens may present later despite gaining entry to the surgical site at the time of the operation. Despite these shortcomings, the ABJHI database is one of the largest institutes that prospectively collects and analyzes data for measuring outcomes against international benchmarks using carefully selected data elements and key performance indicators.

With the rise in THA, an increasing number of patients are at risk of developing a deep SSI involving the joint and adjacent deep tissues. This study reports a rate of deep surgical site infection of 0.2 % in a cohort of patients treated surgically for osteoarthritis of the hip at the 90 d review mark using CDC criteria for diagnosis. This work establishes a reliable population-based baseline infection rate for early-onset deep SSI after THA for osteoarthritis. It also provides valuable insight into risk factors associated with developing an early-onset deep SSI. Although the absolute incidence of deep SSI is low, growing demand for arthroplasty will have substantial implications for service delivery and healthcare costs. In order to successfully devise strategies and interventions that can reduce infection rates and improve outcomes, we must identify patients with modifiable risk factors to counsel and optimize prior to surgery. Use of targeted interventions to influence these risk factors could be effective in reducing the incidence of infection in the future.

This study was reviewed and approved by the local Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board and by the Provincial Health Services Research Department to allow access to patient-specific data.

Data are owned by the Alberta Bone and Joint Health Institute (ABJHI) and cannot be provided without permission by the local Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board and by the Provincial Health Services Research Department to allow access to patient-specific data.

JBM, AJ, and JP designed the study. AS and SP provided statistical expertise. SP performed statistical analysis. JBM, RH, SP, PR, KJ, AJ, and JP analyzed the data. JBM wrote the manuscript draft. RH, SP, PR, KJ, AJ, and JP reviewed and edited the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The Alberta Health Services/Covenant Health Infection Prevention and Control surveillance program is acknowledged.

This paper was edited by Martin Clauss and reviewed by four anonymous referees.

Arthroplasty Collaborative Mac TM: Risk Factors for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Following Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: A 15-Year, Population-Based Cohort Study, J. Bone Joint Surg. Am., 102, 503–509, 2020.

Bozic, K. J., Lau, E., Kurtz, S., Ong, K., Rubash, H., Vail, T. P., and Berry, D. J.: Patient-Related Risk Factors for Periprosthetic Joint Infection and Postoperative Mortality Following Total Hip Arthroplasty in Medicare Patients, J. Bone Joint Surg. Am., 94, 794–800, 2012.

Canadian Institute for Health Information: Surgical Site Infections following Total Hip and Total Knee Replacement Provincial Surveillance: IPC Surveillance and Standards, available at: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/healthinfo/ipc/hi-ipc-sr-hip-knee-ssi-protocol.pdf, last access: 3 May 2020.

Canadian Institute for Health Information: Hip and Knee Replacements in Canada, 2018–2019, Canadian Joint Replacement Registry Annual Report, available at: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/cjrr-annual-statistics-hip-knee-2018-2019-report-en.pdf, last access: 4 May 2021.

CDC/NHSN: Surveillance Definitions for Specific Types of Infections, available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf, last access: 8 May 2021.

Chotanaphuti, T., Courtney, P. M., Fram, B., In den Kleef, N. J., Kim, T. K., Kuo, F. C., Lustig, S., Moojen, D. J., Nijhof, M., Oliashirazi, A., Poolman, R., Purtill, J. J., Rapisarda, A., Rivero-Boschert, S., and Veltman, E. S.: Hip and Knee Section, Treatment, Algorithm: Proceedings of International Consensus on Orthopedic Infections, J. Arthroplast., 34, S393–S397, 2019.

Dale, H., Fenstad, A. M., Hallan, G., Havelin, L. I., Furnes, O., Overgaard, S., Pedersen, A. B., Kärrholm, J., Garellick, G., Pulkkinen, P., Eskelinen, A., Mäkelä, K., and Engesæter, L. B.: Increasing risk of prosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty, Acta Orthop., 83, 449–458, 2012.

Gooch, K. L., Smith, D., Wasylak, T., Faris, P. D., Marshall, D. A., Khong, H., Hibbert, J. E., Parker, R. D., Zernicke, R. F., Beaupre, L., Pearce, T., Johnston, D. W., and Frank, C. B.: The Alberta hip and knee replacement project: a model for health technology assessment based on comparative effectiveness of clinical pathways, Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care, 25, 113–123, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462309090163, 2009.

Gundtoft, P. H., Overgaard, S., Schønheyder, H. C., Møller, J. K., Kjærsgaard-Andersen, P., and Pedersen, A. B.: The “True” Incidence of Surgically Treated Deep Prosthetic Joint Infection After 32,896 Primary Total Hip Arthroplasties: A Prospective Cohort Study, Acta Orthop., 86, 326–334, 2015..

Gundtoft, P. H., Pedersen, A. B., Varnum, C., and Overgaard, S.: Increased mortality after prosthetic joint infection in primary THA, Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res., 475, 2623–2631, 2017.

Harris, W. H.: The first 50 years of total hip arthroplasty, Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res., 467, 28–31, 2009.

Kamath, A. F., Ong, K. L., Lau, E., Chan, V., Vail, T. P., and Rubash, H. E.: Quantifying the Burden of Revision Total Joint Arthroplasty for Periprosthetic Infection, J. Arthroplast., 30, 1492–1497, 2015.

Kunutsor, S. K., Whitehouse, M. R., Blom, A. W., Beswick, A. D. and INFORM Team: Patient-Related Risk Factors for Periprosthetic Joint Infection after Total Joint Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, PLoS One, 11, e0150866, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150866, 2016.

Kurtz, S., Ong, K., Lau, E., Mowat, F., and Halpern, M.: Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030, J. Bone Joint Surg. Am., 89, 780–785, 2007.

Kurtz, S. M., Lau, E., Watson, H., Schmier, J. K., and Parvizi, J.: Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States, J. Arthroplast., 27, 61–65, 2012.

Lenguerrand, E., Whitehouse, M. R., Beswick, A. D., Kunutsor, S. K., Foguet, P., Porter, M., and Blom, A. W.: Revision for prosthetic joint infection following hip arthroplasty: evidence from the National Joint Registry, Bone Joint Res., 6, 391–398, 2017.

Lenguerrand, E., Whitehouse, M. R., Beswick, A. D., Kunutsor, S. K., Burston, B., Porter, M., and Blom, A. W.: Risk factors associated with revision for prosthetic joint infection after hip replacement: a prospective observational cohort study, Lancet Infect. Dis., 18, 1004–1014, 2018.

Mahomed, N. N., Barrett, J. A., Katz, J. N., Phillips, C. B., Losina, E., Lew, R. A., Guadagnoli, E., Harris, W. H., Poss, R., and Baron, J. A.: Rates and outcomes of primary and revision total hip replacement in the United States medicare population, J. Bone Joint Surg. Am., 85, 27–32, 2003.

Manning, L., Metcalf, S., Clark, B., Robinson, J. O., Huggan, P., Luey, C., McBride, S., Aboltins, C., Nelson, R., Campbell, D., Solomon, L. B., Schneider, K., Loewenthal, M., Yates, P., Athan, E., Cooper, D., Rad, B., Allworth, T., Reid, A., Read, K., Leung, P., Sud, A., Nagendra, V., Chean, R., Lemoh, C., Mutalima, N., Grimwade, K., Sehu, M., Torda, A., Aung, T., Graves, S., Paterson, D., and Davis, J.: Clinical Characteristics, Etiology, and Initial Management Strategy of Newly Diagnosed Periprosthetic Joint Infection: A Multicenter, Prospective Observational Cohort Study of 783 Patients, Open Forum Infect. Dis., 7, ofaa068, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaa068, 2020.

Moore, A. J., Blom, A. W., Whitehouse, M. R., and Gooberman-Hill, R.: Deep prosthetic joint infection: a qualitative study of the impact on patients and their experiences of revision surgery, BMJ Open, 5, e009495, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009495, 2015.

Ong, K. L., Kurtz, S. M., Lau, E., Bozic, K. J., Berry, D. J., and Parvizi, J.: Prosthetic joint infection risk after total hip arthroplasty in the Medicare population, J. Arthroplast., 24, 105–109, 2009.

Parvizi, J. and Gehrke, T.,: International Consensus Group on Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Definition of periprosthetic joint infection, J. Arthroplast., 29, 1331, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.009, 2014.

Parvizi, J., Gehrke, T., and Chen, A. F.: Proceedings of the International Consensus on Periprosthetic Joint Infection, Bone Joint J., 95-B, 1450–1452, 2013.

Perfetti, D. C., Boylan, M. R., Naziri, Q., Paulino, C. B., Kurtz, S. M., and Mont, M. A.: Have Periprosthetic Hip Infection Rates Plateaued?, J. Arthroplast., 32, 2244–2247, 2017.

Premkumar, A., Kolin, D. A., Farley, K. X., Wilson, J. M., McLawhorn, A. S., Cross, M. B., and Sculco, P. K.: Projected Economic Burden of Periprosthetic Joint Infection of the Hip and Knee in the United States, J. Arthroplast., 36, 1484–1489, 2021.

Rennert-May, E., Bush, K., Vickers, D., and Smith, S.: Use of a provincial surveillance system to characterize postoperative surgical site infections after primary hip and knee arthroplasty in Alberta, Canada, Am. J. Infect. Control, 44, 1310–1314, 2016.

RStudio Team: RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, available at: http://www.rstudio.com/ (last access: 4 May 2021), 2020.

Rusk, A., Bush, K., Brandt, M., Smith, C., Howatt, A., Chow, B., and Henderson, E.: Improving surveillance for surgical site infections following total hip and knee arthroplasty using diagnosis and procedure codes in a provincial surveillance network, Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol., 37, 699–703, 2016.

Singh, J. A., Yu, S., Chen, L., and Cleveland, J. D.: Rates of Total Joint Replacement in the United States: Future Projections to 2020–2040 Using the National Inpatient Sample, J. Rheumatol., 46, 1134–1140, 2019.

Smith, M., Lix, L. M., Azimaee, M., Enns, J. E., Orr, J., Hong, S., and Roos, L. L.: Assessing the quality of administrative data for research: a framework from the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc., 25, 224–229, 2018.

Tan, T. L., Maltenfort, M. G., Chen, A. F., Shahi, A., Higuera, C. A., Siqueira, M., and Parvizi, J.: Development and Evaluation of a Preoperative Risk Calculator for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Following Total Joint Arthroplasty, J. Bone Joint Surg. Am., 100, 777–785, 2018.

Zimmerli, W., Trampuz, A., and Ochsner, P. E.: Prosthetic-joint infections, N. Engl. J. Med., 351, 1645–1654, 2004.

Zmistowski, B., Karam, J. A., Durinka, J. B., Casper, D. S., and Parvizi, J.: Periprosthetic joint infection increases the risk of one-year mortality, J. Bone Joint Surg. Am., 95, 2177–2184, 2013.

The requested paper has a corresponding corrigendum published. Please read the corrigendum first before downloading the article.

- Article

(145 KB) - Full-text XML