the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Diagnosing pelvic osteomyelitis in patients with pressure ulcers: a systematic review comparing bone histology with alternative diagnostic modalities

Maria Chicco

Prashant Singh

Younatan Beitverda

Gillian Williams

Hassan Hirji

Guduru Gopal Rao

Accurate diagnosis of osteomyelitis underlying pressure ulcers is essential, as overdiagnosis exposes patients to unnecessary and prolonged antibiotic therapy, while failure to diagnose prevents successful treatment. Histopathological examination of bone biopsy specimens is the diagnostic gold standard. Bone biopsy can be an invasive procedure, and, for this reason, other diagnostic modalities are commonly used. However, their accuracy is questioned in literature.

This systematic review aims to assess accuracy of various modalities (clinical, microbiological and radiological) for the diagnosis of pelvic osteomyelitis in patients with pressure ulcers as compared to the gold standard.

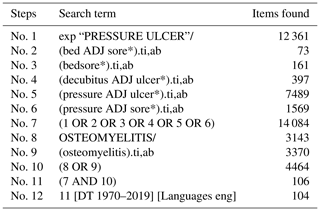

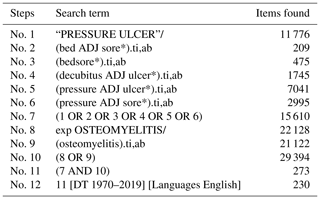

A systematic literature search was conducted in July 2019 using the MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System – MEDLARS – Online) and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) databases. The search terms were “decubitus ulcer”, “pressure ulcer”, “pressure sore”, “bedsore” and “osteomyelitis”. The inclusion criteria were original full-text articles in English comparing the results of bone histology with those of other diagnostic modalities in adult patients with pelvic pressure ulcers.

Six articles were included in the systematic review. Clinical diagnosis was found to be neither specific nor sensitive. Microbiological examination, and in particular cultures of bone biopsy specimens, displayed high sensitivity but low specificity, likely reflecting contamination. Radiological imaging in the form of X-ray and CT (computed tomography) scans displayed high specificity but low sensitivity. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), bone scanning and indium-labelled scintigraphy displayed high sensitivity but low specificity.

Our systematic review did not find any diagnostic method (clinical, microbiological or radiological) to be reliable in the diagnosis of pelvic osteomyelitis associated with pressure ulcers as compared to bone histology.

- Article

(364 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Pressure ulcers are caused by injury to the skin and underlying tissue, due to external forces such as pressure and/or shearing forces (Edsberg et al., 2016). They often occur in areas of bony prominence, such as the sacrum (Vanderwee et al., 2007). Patients at risk of pressure ulceration include those with spinal cord injuries (SCIs) and those with limited mobility, such as older people (Gefen, 2014; Bergstrom et al., 1998).

The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP), the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) and the Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA) have agreed on a definition and categorisation of pressure injuries. These state that pressure ulcers vary in severity from non-blanchable erythema of intact skin (grade 1) and partial-thickness skin loss with exposed dermis (grade 2) to full-thickness skin loss (grade 3) and full-thickness skin and tissue loss (grade 4) (Edsberg et al., 2016).

Pressure ulcers carry substantial morbidity and present a significant financial burden for healthcare systems. Between April 2015 and March 2016, 24 674 patients were reported to have developed a new pressure ulcer in the NHS (National Health Service) in England (NHS Improvement, 2018). In 2012, the estimated cost of treating a pressure ulcer varied between GBP 1214 (grade 1) and GBP 14 108 (grade 4) (Dealey et al., 2012), while the estimated NHS expenditure for treating pressure damage amounts to more than GBP 3.8 million per day (NHS Improvement, 2018).

Osteomyelitis can develop in bone underlying pressure ulcers. Treatment of osteomyelitis is complex and often involves prolonged antibiotic courses of 6 or more weeks and repeated surgical procedures. In order to optimise outcomes and treat possible recurrence, these patients need to be treated in a specialised institution by a dedicated interdisciplinary team including infectious-disease clinicians, orthopaedic and plastic surgeons (Dudareva et al., 2017).

Accurate diagnosis of osteomyelitis underlying pressure ulcers is essential, as overdiagnosis exposes patients to unnecessary and prolonged treatment with antibiotics, while failure to diagnose prevents successful treatment. Histopathological examination of bone biopsy specimens is the gold standard for diagnosis. However, bone biopsy can be an invasive procedure and requires the involvement of surgeons in order to be carried out optimally with the collection of multiple specimens for microbiological and histopathological examination.

For this reason, alternative diagnostic modalities are commonly used in clinical practice. These include clinical assessment, microbiological (bone and tissue cultures) and radiological (X-ray, CT – computed tomography – scan, MRI – magnetic resonance imaging, bone scan and scintigraphy) investigations. However, the accuracy of these methods has been questioned in literature (Livesley and Chow, 2002; Wong et al., 2019). This systematic review aims to assess the accuracy of these modalities for the diagnosis of pelvic osteomyelitis in patients with pressure ulcers as compared to the gold standard, i.e. bone histology.

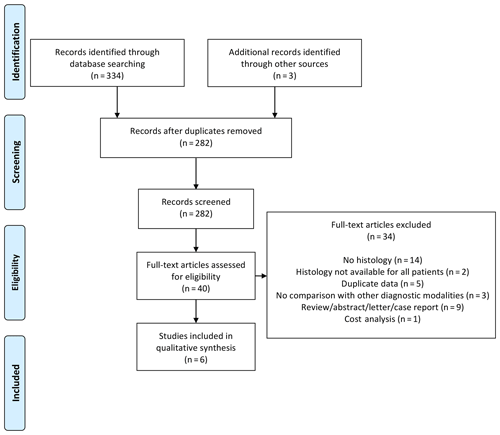

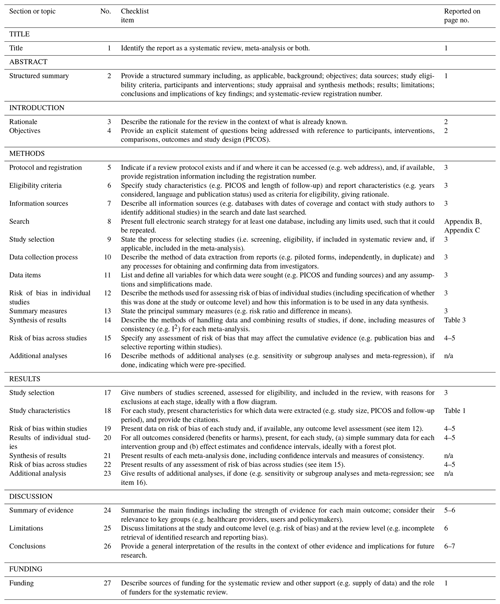

For a high standard of reporting, we followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Details of PRISMA guideline compliance are presented in Appendix A.

2.1 Search strategy

The protocol for this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; CRD42019140299). A systematic literature search was conducted in July 2019 using MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System – MEDLARS – Online) and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) databases. The search terms used were “decubitus ulcer”, “pressure ulcer”, “pressure sore”, “bedsore” and “osteomyelitis” (see the full search strategy in Appendix B and Appendix C). No date limit was applied.

2.2 Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: original full-text articles in English comparing the results of bone histology with those of other diagnostic modalities in adult patients with pelvic pressure ulcers. Studies conducted on the paediatric population were excluded, as were studies that did not report bone histology results or comparison with other diagnostic modalities. The search results were screened in order to identify eligible articles; these were read in full and assessed according to the criteria mentioned above. References were also screened, so as to identify further eligible articles. Disagreement was resolved by consensus or, in its absence, by the senior author.

2.3 Data extraction

The following data were extracted for each article: author; journal; publication year; study design; number of patients and of pressure ulcers; grade and site; prevalence of osteomyelitis; and, for each diagnostic modality, true positive, true negative, false positive and false negative values, as well as sensitivity and specificity. Both authors extracted data independently.

2.4 Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the sensitivity and specificity of the considered diagnostic modalities (clinical, microbiological and radiological) as compared to the gold standard.

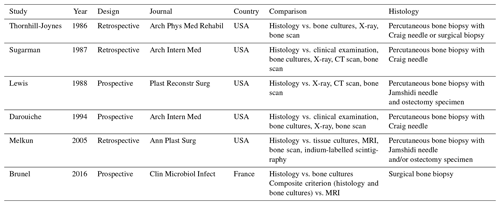

3.1 Search results

Our systematic search identified 334 articles: 40 articles were read in full, and 6 articles were eventually included (see PRISMA diagram in Fig. 1) – 16 articles were excluded specifically due to the absence of histological data. The six studies included were published between 1986 and 2016 (Thornhill-Joynes et al., 1986; Sugarman, 1987; Lewis et al., 1988; Darouiche et al., 1994; Melkun and Lewis, 2005; Brunel et al., 2016). Most were conducted in the USA and involved retrospective review of patient records (see Table 1).

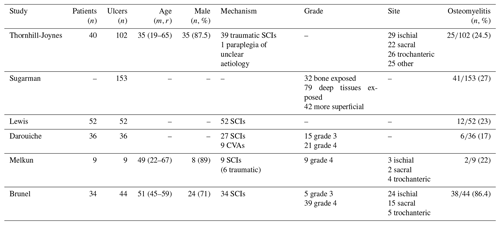

3.2 Demographic data

Demographic data are limited, but those available are presented in Table 2: the majority of patients included in the studies were SCI patients, male and comparatively young. One study included only grade 4 pressure ulcers, while two studies included both grade 3 and 4, and three studies did not specifically mention the pressure ulcer grade. Given the small number of studies meeting the inclusion criteria, we decided to retain the six studies irrespective of pressure ulcer grade. Prevalence of osteomyelitis ranged from 17 % to 86 %, with most studies reporting a prevalence of approximately 20 %.

3.3 Histology

Histological diagnosis of osteomyelitis was defined by the presence of inflammatory cells (either polymorphonuclear leucocytes in acute infection or mononuclear leukocytes in chronic infection) – all studies except one (Melkun and Lewis, 2005) specifically mentioned adhering to this definition. Bone biopsies for histological examination were obtained by a variety of methods (see Table 1): one study obtained surgical biopsies, four studies obtained percutaneous biopsies using a Craig or Jamshidi needle and one study obtained either percutaneous or surgical biopsies. Two studies obtained both percutaneous needle biopsies and ostectomy specimens after patients underwent bone excision and soft-tissue reconstruction. Melkun and Lewis noted that “in all cases where both ostectomy specimens and bone biopsy were available, the results were consistent” (Melkun and Lewis, 2005). Lewis et al. (1988) reported a sensitivity of 73 % and specificity of 96 % for needle biopsy as compared to ostectomy.

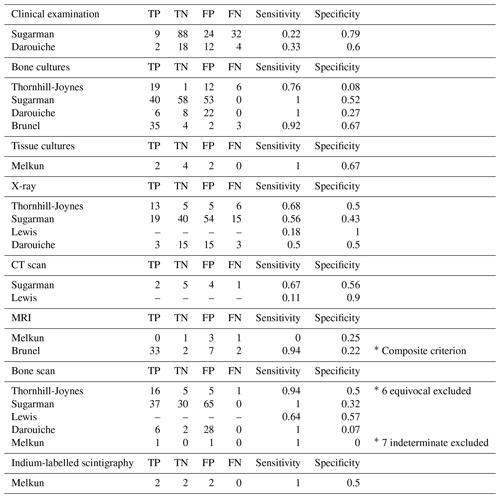

3.4 Clinical examination

Two studies assessed the sensitivity and specificity of clinical examination compared to histology of bone biopsies. In the first study, one infectious-disease clinician assessed patients prior to biopsy: clinical signs suggestive of osteomyelitis included “grossly purulent drainage, advancing erythematous border, or systemic signs of infection attributed to pressure sore” (Sugarman, 1987). The sensitivity and specificity of clinical examination were 22 % and 79 %, respectively. In the second study, one infectious-disease clinician and one orthopaedic surgeon independently assessed patients for ulcer duration, bone exposure, purulent discharge and fever. The sensitivity and specificity of clinical examination were 33 % and 60 %, respectively (Darouiche et al., 1994).

3.5 Bone and tissue cultures

Four studies compared bone cultures, defined as bone biopsy specimens used for culture, and histology results: sensitivity ranged from 76 % to 100 %, and specificity ranged from 8 % to 67 % (see Table 3). Brunel et al. (2016) considered a bone culture positive if one sample grew non-commensal bacteria or if three samples grew the same commensal bacteria. Using these criteria, they found good agreement between histology and microbiology (κ=0.55) (Brunel et al., 2016). One study reported on the results of tissue cultures: sensitivity was 100 %, and specificity was 67 % (Melkun and Lewis, 2005).

3.6 X-ray and CT

Four studies reported on the sensitivity and specificity of X-ray for the diagnosis of osteomyelitis: sensitivity ranged from 18 % to 68 %, and specificity ranged from 43 % to 100 %. Two studies also performed CT scanning: sensitivity ranged from 11 % to 67 %, and specificity ranged from 56 % to 90 %.

3.7 MRI

Two studies assessed the sensitivity and specificity of MRI: sensitivity differed greatly between studies, with one study reporting a value of 94 % and the other reporting 0 %. Specificity on the other hand was similar between studies – 22 % and 25 %. The study reporting a sensitivity of 0 % only included five patients for which both histological and MRI data were available (Melkun and Lewis, 2005). The other study used a composite criterion of histology and bone cultures to diagnose osteomyelitis (Brunel et al., 2016).

3.8 Bone scan

Five studies evaluated technetium bone scans as a diagnostic modality. Reported sensitivity ranged from 64 % to 100 %, and specificity ranged from 0 % to 57 %. In two studies, an important number of bone scans were reported as “equivocal” or “indeterminate” and were not considered in the analysis (Thornhill-Joynes et al., 1986; Melkun and Lewis, 2005).

3.9 Scintigraphy

One study assessed indium-labelled autologous leukocyte scintigraphy: sensitivity was 100 %, and specificity was 50 %. Three scans were reported as “inconclusive” and excluded from the results (Melkun and Lewis, 2005).

Although osteomyelitis is a recognised serious complication of pressure ulcers, our review shows that little attention is currently focused on the diagnosis of this condition. Of the 40 articles screened in our review, the majority (21 of 40) were published in the 1980s and 1990s. Few studies have been published in the past 2 decades. The paucity of research on this topic has led some authors to describe pressure-ulcer-related osteomyelitis as a “neglected disease of the developed world” (Bodavula et al., 2015).

The gold standard for diagnosis of pressure-ulcer-related osteomyelitis is histological examination of bone biopsy specimens (Livesley and Chow, 2002). Histopathology can distinguish between osteomyelitis – characterised by the presence of inflammatory cell infiltrates – and pressure-related bone changes, such as fibrosis and reactive bone formation, which are inevitably present within grade 4 pressure ulcers even when cortical bone is intact (Türk et al., 2003).

In clinical practice, alternatives to bone histology such as clinical, microbiological and radiological modalities are commonly used. Our review sought to systematically compare results of these alternative modalities with the gold standard in order to evaluate their accuracy and usefulness.

Clinical examination displayed both low sensitivity and low specificity. Osteomyelitis can be difficult to distinguish clinically from the infection of soft tissues; at the same time, soft-tissue involvement may underestimate the degree of underlying bone involvement, as the pressure exerted on the skin is distributed over a wider bone surface (Livesley and Chow, 2002).

Pressure-ulcer-related osteomyelitis is often polymicrobial and can be caused by gram negative and anaerobes, as well as more usual bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and pyogenic streptococci (Sugarman, 1987; Brunel et al., 2016). However, identifying the causative pathogen can be challenging, as pelvic pressure ulcers are often colonised with commensal bacteria of the skin and digestive tract (Deloach et al., 1992). Cultures of bone biopsy specimens represent the cornerstone of osteomyelitis treatment: isolation of the same bacteria from multiple intra-operative samples is essential to target antibiotic therapy.

For diagnostic purposes, cultures of bone biopsy specimens in our review displayed high sensitivity but low specificity, likely reflecting contamination. It is important to note, however, that only one of the included studies reported a strict antibiotic-free period before bone biopsy (Brunel et al., 2016). Bone sampling methods and microbiological interpretation criteria of cultures to distinguish between causative bacteria and contamination varied across studies. These factors may have affected the accuracy of bone cultures as a diagnostic modality in our study. Using multiple specimens with stringent microbiological criteria for the collection, processing of specimens and interpretation of culture results, Brunel et al. (2016) found good agreement between bone cultures and histology. The role of improved microbiological culture methods, such as sonification to dislodge biofilms and non-culture methods to detect 16S ribosomal RNA (which are used for diagnosis of prosthetic-joint infection), have not been studied in the context of pelvic osteomyelitis secondary to pressure ulcers.

Radiological imaging in the form of X-ray and CT scans displayed high specificity but low sensitivity. False negative rates can be high, in particular with X-ray, as early bone erosion may not be detected (Thornhill-Joynes et al., 1986). On the other hand, MRI, bone scanning and indium-labelled scintigraphy displayed high sensitivity but low specificity. In fact, these imaging techniques may not be able to distinguish between osteomyelitis, soft-tissue inflammation and pressure-related bone changes, e.g. cortical bone erosion and bone marrow oedema (Ruan et al., 1998; Wheat, 1985).

Our systematic review suggests that no diagnostic modality offers a sufficiently accurate alternative to bone histology, which remains the gold standard. Therefore, diagnosing pressure-ulcer-related osteomyelitis on the basis of any modality other than bone histology runs the risk of over- or underdiagnosis. While overdiagnosis can expose patients to unnecessary and prolonged antibiotic treatment, failure to diagnose osteomyelitis can jeopardise the successful treatment and healing of pressure ulcers (Han et al., 2002).

A recent study showed that diagnostic approaches to pressure-ulcer-related osteomyelitis vary significantly among infectious-disease clinicians, an important proportion of whom reported low confidence in making this diagnosis. The authors suggest that this reflects the lack of evidence and of agreed diagnostic criteria for this condition (Kaka et al., 2019). This is in contrast with osteomyelitis associated with diabetic foot ulcers, where recognised diagnostic criteria exist and recommendations include performing transcutaneous or surgical bone biopsy for histological and microbiological examination (Lipsky et al., 2012).

Our review has several limitations: a small number of studies, mostly of retrospective design, including a low number of patients. The majority of studies were conducted in SCI patients, and this may affect the generalisability of results to older people, who represent the main population affected by pressure ulcers. Furthermore, while it is generally agreed that osteomyelitis develops in grade 4 pressure ulcers, the selected studies included both grade 3 and 4 pressure ulcers or did not specify pressure ulcer grade; this may further affect the generalisability of our results.

In our systematic review, we did not find any alternative diagnostic method (clinical, microbiological or radiological) to be reliable in the diagnosis of osteomyelitis associated with pelvic pressure ulcers.

Clinical diagnosis is neither specific nor sensitive. Microbiological examination, in particular, bone cultures, displayed high sensitivity but low specificity, likely reflecting contamination. Use of multiple bone specimens collected appropriately, processed using agreed protocols with culture results interpreted using validated criteria, may increase the accuracy of microbiological examination. Radiological imaging in the form of X-ray and CT scans displayed high specificity but low sensitivity. MRI, bone scanning and indium-labelled scintigraphy displayed high sensitivity but low specificity.

To avoid unnecessary and prolonged antibiotic therapy or a failure to treat osteomyelitis, it is important that clinicians should be aware of the limitations of clinical and radiological diagnostic modalities. Microbiological examination is also unreliable unless it is undertaken appropriately using bone biopsies. Further research is necessary to identify improved strategies for the accurate diagnosis of osteomyelitis in patients with pelvic pressure ulcers.

All data are presented in the tables and figures.

MC and GR designed the study and wrote the paper. MC and PS collected and analysed the data. YB, GW and HH reviewed and critically revised the paper.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the staff from Northwick Park Hospital John Squire Library, in particular Michael Kendall and Fraser Williams, for their assistance in conducting the search and sourcing literature.

This paper was edited by Parham Sendi and reviewed by Eric Senneville and one anonymous referee.

Bergstrom, N., Braden, B., Kemp, M., Champagne, M., and Ruby, E.: Predicting pressure ulcer risk: a multisite study of the predictive validity of the Braden Scale, Nurs. Res., 47, 261–269, https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199809000-00005, 1998.

Bodavula, P., Liang, S. Y., Wu, J., VanTassell, P., and Marschall, J.: Pressure Ulcer-Related Pelvic Osteomyelitis: A Neglected Disease?, Open Forum Infect. Dis., 2, ofv112, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofv112, 2015.

Brunel, A. S., Lamy, B., Cyteval C, Perrochia, H., Téot, L., Masson, R., Bertet, H., Bourdon, A., Morquin, D., Reynes, J., Le Moing, V., and OSTEAR Study Group: Diagnosing pelvic osteomyelitis beneath pressure ulcers in spinal cord injured patients: a prospective study, Clin. Microbiol. Infec., 22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2015.11.005, 2016.

Darouiche, R. O., Landon, G. C., Klima, M., Musher, D. M., and Markowski, J.: Osteomyelitis associated with pressure sores, Arch. Intern. Med., 154, 753–758, https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1994.00420070067008, 1994.

Dealey, C., Posnett, J., and Walker, A.: The cost of pressure ulcers in the United Kingdom, J. Wound Care, 21, 261–266, https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2012.21.6.261, 2012.

Deloach, E. D., DiBenedetto, R. J., Womble, L., and Gilley, J. D.: The treatment of osteomyelitis underlying pressure ulcers, Decubitus, 5, 32–41, 1992.

Dudareva, M., Ferguson, J., Riley, N., Stubbs, D., Atkins, B., and McNally, M.: Osteomyelitis of the pelvic bones: a multidisciplinary approach to treatment, J. Bone Joint Infect., 2, 184–193, https://doi.org/10.7150/jbji.21692, 2017.

Edsberg, L. E., Black, J. M., Goldberg, M., McNichol, L., Moore, L., and Sieggreen, M.: Revised National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel Pressure Injury Staging System: Revised Pressure Injury Staging System, J. Wound. Ostomy. Cont., 43, 585–597, https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000281, 2016.

Gefen, A.: Tissue changes in patients following spinal cord injury and implications for wheelchair cushions and tissue loading: a literature review, Ostomy Wound Manag., 60, 34–45, 2014.

Han, H., Lewis Jr., V. L., Wiedrich, T. A., and Patel, P. K.: The value of Jamshidi core needle bone biopsy in predicting postoperative osteomyelitis in grade IV pressure ulcer patients, Plast. Reconstr. Surg., 110, 118–122, https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200207000-00021, 2002.

Kaka, A. S., Beekmann, S. E., Gravely, A., Filice, G. A., Polgreen, P. M., and Johnson, J. R.: Diagnosis and management of osteomyelitis associated with stage 4 pressure ulcers: report of a query to the Emerging Infections Network of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Open Forum Infect. Dis., 6, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz406, 2019.

Lewis Jr., V. L., Bailey, M. H., Pulawski, G., Kind, G., Bashioum, R. W., and Hendrix, R. W.: The diagnosis of osteomyelitis in patients with pressure sores, Plast. Reconstr. Surg., 81, 229–232, https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198802000-00016, 1988.

Lipsky, B. A., Berendt, A. R., Cornia, P. B., Pile, J. C., Peters, E. J., Armstrong, D. G., Deery, H. G., Embil, J. M., Joseph, W. S., Karchmer, A. W., Pinzur, M. S., Senneville, E., and Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections, Clin. Infect. Dis., 54, 132–173, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis346, 2012.

Livesley, N. J. and Chow, A. W.: Infected pressure ulcers in elderly individuals, Clin. Infect. Dis., 35, 1390–1396, https://doi.org/10.1086/344059, 2002.

Melkun, E. T. and Lewis Jr., V. L.: Evaluation of (111) indium-labeled autologous leukocyte scintigraphy for the diagnosis of chronic osteomyelitis in patients with grade IV pressure ulcers, as compared with a standard diagnostic protocol, Ann. Plast. Surg., 54, 633–636, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sap.0000164467.97551.ed, 2005.

NHS Improvement: Pressure ulcers: revised definition and measurement Summary and recommendations, available at: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2932/NSTPP_summary_recommendations_2.pdf (last access: 29 May 2020), 2018.

Ruan, C. M., Escobedo, E., Harrison, S., and Goldstein, B.: Magnetic resonance imaging of nonhealing pressure ulcers and myocutaneous flaps, Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab., 79, 1080–1088, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90175-7, 1998.

Sugarman, B.: Pressure sores and underlying bone infection, Arch. Intern. Med., 147, 553–555, https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1987.00370030157030, 1987.

Thornhill-Joynes, M., Gonzales, F., Stewart, C.A., Kanel, G. C., Lee, G. C., Capen, D. A., Sapico, F. L., Canawati, H. N., and Montgomerie, J. Z.: Osteomyelitis associated with pressure ulcers, Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab., 67, 314–318, 1986.

Türk, E. E., Tsokos, M., and Delling, G.: Autopsy-based assessment of extent and type of osteomyelitis in advanced-grade sacral decubitus ulcers: a histopathologic study, Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med., 127, 1599–1602, 2003.

Vanderwee, K., Clark, M., Dealey, C., Gunningberg, L., and Defloor, T. Pressure ulcer prevalence in Europe: a pilot study, J. Eval. Clin. Pract., 13, 227–235, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00684.x, 2007.

Wheat, J.: Diagnostic strategies in osteomyelitis, Am. J. Med., 78, 218–224, https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(85)90388-2, 1985.

Wong, D., Holtom, P., and Spellberg, B.: Osteomyelitis Complicating Sacral Pressure Ulcers: Whether or Not to Treat With Antibiotic Therapy, Clin. Infect. Dis., 68, 338–342, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy559, 2019.