the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Pubic bone osteomyelitis outcomes in patients with malignancies: a case series from an academic cancer center

Alexander M. Lewis

Max Vaynrub

Peter A. Mead

Melanie Betchen

Mini Kamboj

Anna Kaltsas

Introduction: Pubic bone osteomyelitis (PBO) is a rare complication with sometimes delayed development in patients who have received radiotherapy or surgery of the pelvic region for cancer treatment. Treatment options range from antibiotics alone to pubic bone debridement and source control via diversion of gastrointestinal (GI) or genitourinary (GU) tract fistulae. In this single-center case series of patients with cancer, we sought to characterize outcomes of PBO. Methods: We conducted a retrospective analysis of 26 patients, admitted for PBO to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center between 2017 and 2024. Demographic, clinical presentation, microbiology, treatment, and outcome data were evaluated. Patients were followed until date of death or date of last follow-up. Results: Of the 26 patients, 23 were male (88 %) and 3 were female (12 %), with a median age at diagnosis of 70.5 years. The median follow-up period was 680 d. 18/26 (69 %) had fistulas to the pubic bone. 15 patients (58 %) received antibiotics alone. 11 patients (42 %) underwent pubic bone debridement; 8 underwent additional GI or GU diversion procedures for source control. In the group who received surgery, 9/11 (81 %) were ambulating without assistive devices at end of follow-up. In those receiving antibiotics alone, 9/15 (60 %) died a median of 466 d from diagnosis of PBO. Conclusion: In our case series, a combination of surgical debridement plus targeted antibiotic therapy offered the best outcomes. However, some patients achieved improvement in symptoms with antibiotic management alone when more aggressive surgical interventions were not feasible.

- Article

(629 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis is a rare infectious inflammatory condition that makes up less than 1 % of all osteomyelitis cases, and, if left untreated, it can lead to significant long-term morbidity and, rarely, become potentially life threatening (Ross and Hu, 2003; Peltola and Pääkkönen, 2014; Wechsler et al., 2021). Risk factors for pubic bone osteomyelitis (PBO) include current or past pelvic malignancy, osteoradionecrosis from pelvic radiation, and urological or other pelvic surgery (Wechsler et al., 2021; Hansen et al., 2022). Tumor- or surgery-related anatomic disruptions can form genitourinary (GU) or gastrointestinal (GI) fistulas and lead to microbial seeding of the pubic bones and progressive infection. Radiographically, PBO manifests as bone edema, cortical erosion, abscess formation, and septic arthritis of the pubic symphysis. The presentation of PBO typically involves pain in the anterior pubis, but patients can also experience pain in other areas of the pelvis, including groin, upper thighs, abdomen, hips, or lower back, usually accompanied by difficulty in walking, which may become progressive and irreversible (Ross and Hu, 2003; Pham and Scott, 2007; Hawkins et al., 2015; Shu et al., 2021).

Given the relative rarity of this infection, there are no guidelines to suggest best management practices for this entity specifically. Even less data exist on best practices in patients who are unable to undergo aggressive surgeries for source control and debridement of infected bone, due to underlying co-morbidities or poor overall health status, as is often the case in patients with cancer. Currently published society guidelines focus only on vertebral osteomyelitis (Berbari et al., 2015) or speak more generically to pyogenic osteomyelitis but not specifically to the management of pubic bone osteomyelitis (Spellberg et al., 2022).

Best practices for PBO management are crucial to aid in early diagnosis, attempt curative treatment and improve outcomes, preserve mobility, and ensure optimal symptom alleviation (Upadhyayula, 2020; Wechsler et al., 2021). Due to its subtle and insidious onset, PBO diagnosis is often delayed. Failure to identify and treat PBO early in its pathogenesis can result in ongoing bone and joint destruction, compromising the integrity of the pubic symphysis and pelvic structures, potentially leading to pelvic ring instability, impaired load transfer, sacral insufficiency fractures, and irreversible joint and ligamentous damage (Sexton et al., 1993; Gupta et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2021; Devlieger et al., 2021; Sambri et al., 2021).

In addition, there is a paucity of literature on the treatment of PBO specifically in people with cancer who may have unique risk factors related to surgical or tumor-related anatomic predisposition, radiation, and chemotherapy. Due to the complex nature of the infection, pubic bone debridement, the mainstay of osteomyelitis management, may not always be feasible or safe (Romanò et al., 2010). On the other hand, if only antibiotics are used for treatment, microbial eradication may not be achieved (Smeyers et al., 2024). Therefore, the clinical characterization of the risks and outcomes of this rare bone infection with myriad presentations is essential to provide the best outcomes for patients and minimize long-term morbidity (Upadhyayula, 2020; Wechsler et al., 2021).

In the present retrospective case series, we sought to evaluate outcomes of PBO in a cancer patient population. We performed a retrospective case series of 26 consecutive patients treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center from 2017 to 2024.

We retrospectively studied all patients who had an infectious disease consult requested for pubic bone osteomyelitis (PBO) at our institution between January 2017 and December 2024, by querying the infectious disease consult database. PBO was defined by its presence on X-ray, CT, or MRI as interpreted by the reading radiologist as probable osteomyelitis using the terms “bony destruction,” and “pubic symphysis cortical erosion or diastasis” or by chart review when an orthopedic surgeon or infectious disease specialist also made the clinical diagnosis of PBO based on imaging, physical exam findings, and culture results. Demographic data were extracted from charts, including age of diagnosis, sex, co-morbidities, smoking status, cancer diagnoses, prior cancer-related treatment including radiation, date of last radiation, previous urethral manipulations, the presence of indwelling urinary hardware at PBO diagnosis, previous pelvic surgery, symptoms on presentation, and the days from the last cancer treatment (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or surgery) to PBO diagnosis. Treatment variables were evaluated, including whether an interventional radiologist acquired a bone biopsy or aspiration, whether surgical debridement was performed, and the type and duration of antibiotic therapy.

History of radiation therapy involved any radiation to the abdominal or pelvic area prior to PBO diagnosis. Timing of pelvic radiation relative to date of PBO diagnosis was also recorded.

Tissue, blood, and bone culture patient samples were tracked from the date closest to diagnosis, and cultures that were positive were used to guide antibiotic management.

Patients in the antibiotics-only group were defined by the absence of orthopedic surgical intervention (pubic bone debridement and/or addressing any fistulae) for the treatment of PBO, except for obtaining bone or tissue biopsies for cultures.

Patients in the pubic bone debridement group underwent surgical intervention as defined by pubic bone debridement in addition to antibiotic administration, and in cases where they also received additional urinary or colorectal diversion procedures, this was also recorded.

Patients were followed through date of death or date of last follow-up at our institution. Treatment outcomes were defined as ambulating with or without assistance at time of last follow-up at our institution and whether or not they were described as having any pubic-bone-related pain (pain in the pelvis, in the groin, or radiating down the legs) in clinical notes at the time of last follow-up. General outcomes such as whether there was progression of pubic bony destruction on last imaging prior to death or last follow-up was tracked, and mortality status was also recorded.

Descriptive statistics were performed by describing the number of patients in each statistical category with a percentage of their respective group sample and by calculating the median and interquartile range (IQR).

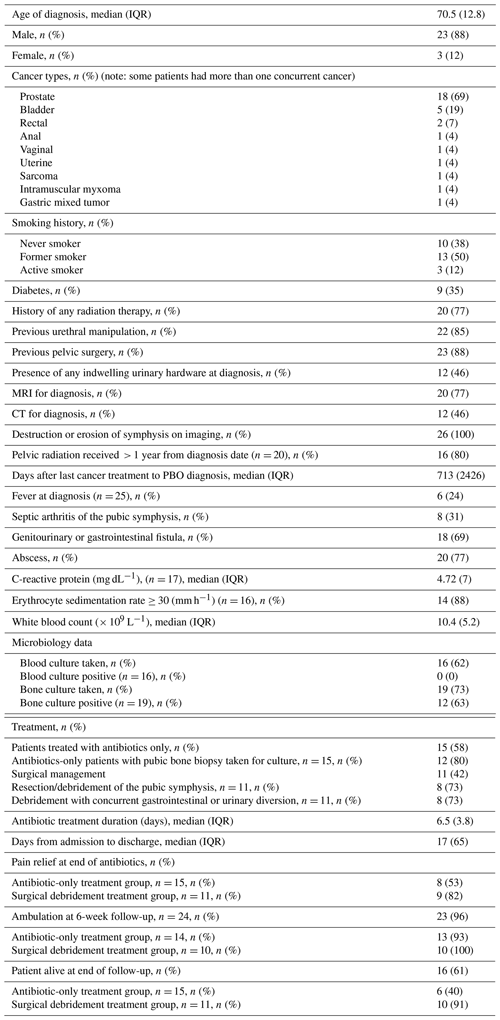

Between January 2017 and December 2024, 26 patients met the search criteria for PBO; among these, 23 were males (88 %) and 3 were females (12 %). The median (interquartile range (IQR)) for the age of diagnosis was 70.5 (12.8), with a range of 34 to 85 years old. Underlying cancer, co-morbid conditions, and other clinical characteristics at presentation are shown in Table 1.

Imaging modalities used for PBO diagnosis included MRI for 14 patients (54 %), CT for 5 patients (19 %), MRI and CT for 6 patients (23 %), and CT and X-ray for 1 patient (4 %). All patients had destruction or erosion of the pubic bone and/or symphysis by imaging. Most patients (18/26, 69 %) had either a genitourinary (GU) or gastrointestinal (GI) fistula interacting with the pubic symphysis on imaging, and 20 (77 %) had an abscess.

All patients had at least one cancer diagnosis, the most common being either prostate (54 %) or bladder cancer (8 %), with one patient each having non-genitourinary-related cancers, including rectal, leiomyosarcoma, anal, uterine, and vaginal. Some patients had more than one cancer. 20 patients (77 %) had received previous radiation therapy to the pelvic area, and 23 of the 26 (88 %) had previous pelvic surgeries, including genitourinary tract procedures such as stents. More than 80 % of those who had a history of pelvic radiation had received it more than 1 year prior to PBO diagnosis. Notably, there was a large date range from the date of last cancer-directed therapy to the date of PBO diagnosis, with a range of 50 to 7244 d (median: 460 d). In one patient, it was nearly 20 years from the date of last cancer-directed therapy that they presented with pubic bone osteomyelitis.

In terms of presenting symptoms, the most common symptoms included, in 96 % of patients, difficulty ambulating and chronic and/or excruciating pain of the pubic area, suprapubic area, pelvis, hips, back, abdomen, groin, buttocks, or perineum. Fever was uncommon. In a single case, PBO was asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally on CT imaging, followed by MRI and culture results.

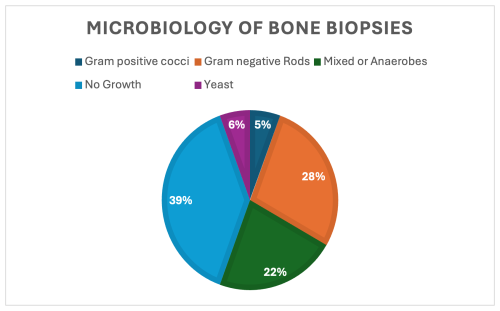

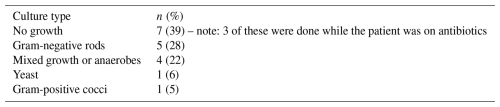

In terms of laboratory findings at time of diagnosis, the median (IQR) value for CRP at the date closest to PBO diagnosis of 17 patients was 4.72 mg dL−1 (7), and WBC was 10.4 × 109 L−1 (5.2) on the date of diagnosis. Of 16 patients where ESR data were available, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate ≥ 30 mm h−1 was present in 14 patients (88 %). None of these patients had bacteremia. Of the 19 who did have bone biopsies, 12 had either a positive gram stain or growth in cultures for a 63 % positivity rate, and in 11 cases an organism was isolated in culture (Table 2). Target amplicon sequencing was not pursued in any of the cases. Of the 7 patients who had no growth in bone biopsies, 3 of them were already on antibiotics at the time of biopsy. There were 3 patients whose bone cultures grew organisms despite being on antibiotics at the time of biopsy as well. Aggregate microbiology results are displayed in Fig. 1 and Table 2.

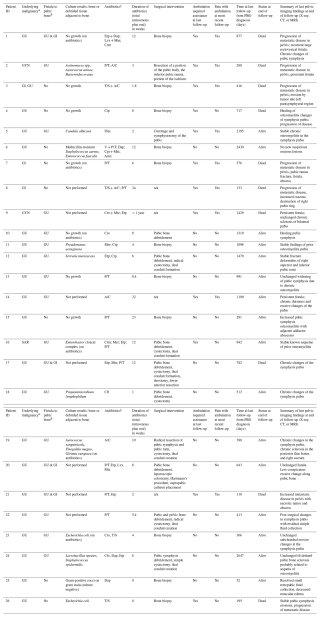

For the treatment of PBO, in most cases extended antibiotic courses were used (median 49 d). The median (IQR) number of days from hospital admission to discharge for PBO assessment and treatment was 6.5 (3.8 d). Surgical approaches were varied. The bone biopsies were sent either by interventional radiologists or by orthopedic surgeons at the time of debridement. Descriptions of surgical interventions are included in Table 3.

Antibiotic regimens were determined by an infectious disease specialist and were individualized, and decisions were based on whether source control was achieved. The treatment regimens, durations, and outcomes are listed in Table 3.

Table 3Individual patient characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Note that n/a represents not applicable.

Abbreviations: a Malignancy: GU = genitourinary; GYN = gynecological; GI = gastrointestinal; SAR = sarcoma. b Fistula: GU = genitourinary; GI = gastrointestinal. c Antibiotics: A/C = amoxicillin/clavulanate;

Amx = amoxicillin; Cfl = cephalexin; Cfz = cefazolin; cip = ciprofloxacin; crm = cefuroxime; cro = ceftriaxone; Dap = daptomycin; Etp = ertapenem; Fluc = fluconazole; Lvx = levofloxacin; Mer = meropenem;

Min = minocycline; Mtz = metronidazole; P/T = piperacillin/tazobactam; T/S = trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Patients were followed until death or date of last follow-up (median of 680 d; range: 52 to 2647 d). Outcomes were evaluated at the time of last follow-up. 10 out of 26 (38 %) patients had died at the end of follow-up.

Among the 15 patients (58 %) treated with antibiotics alone, 8/15 (53 %) had no pubic-bone-related pain at time of last follow-up, with 6/15 (40 %) walking without an assistive device at time of last follow-up. However, 9 of these 15 patients had died at the time of last follow-up, comprising 82 % of the total deaths in this case series. 8 of these 9 patients who died in this group had persistent fistulae, progression of malignant disease, and/or continued signs of abscesses and pubic bone destruction on the last imaging study (X-ray, CT, or MRI) before death.

There were 11 patients (42 %) who underwent pubic bone debridement, with 8/11 undergoing additional procedures such as cystectomy, ileal conduit creation, or colostomy creation for diversion of urine or gastrointestinal flora away from the pubic bone in addition to pubic bone debridement. Of the patients who had surgical interventions plus antibiotic treatment, 7/11 (63 %) had no pubic-bone-related pain at date of last follow-up, and 9/11 (81 %) were ambulating without an assistive device at time of last follow-up. 1 of these 11 patients had died at the time of last follow-up, comprising 10 % of the total deaths in this case series.

Pubic bone osteomyelitis (PBO) is a rare complication that can occur after the treatment of cancers in the pelvis, either due to radiotherapy received in that region and/or pelvic or urologic surgical procedures previously performed to address a primary cancer. Despite the rarity of PBO as a complication following cancer treatment, it is important to promptly diagnose and employ a multidisciplinary approach to management to ensure the best outcomes. In our case series, patients diagnosed early with definitive surgical management that included source control and bone debridement had the best outcomes. These data support previous clinical data which also correlate better treatment outcomes with pubic bone debridement plus antibiotics (Gupta et al., 2015; Lavien et al., 2017; Nosé et al., 2020; Devlieger et al., 2021; Shu et al., 2021; Ambrosini et al., 2022; Hansen et al., 2022; Walach et al., 2024). Those who were frail, with advanced cancer and high risk for surgical debridement, still achieved some symptom palliation from antibiotic management alone.

A caveat to these findings is that the patients who did not undergo pubic bone debridement and instead were managed conservatively with antibiotics alone were likely to be in an overall sicker group, perhaps with poorer prognoses related to their malignancies, and this likely influenced decisions regarding surgery.

Among risk factors for PBO in the oncology setting, advanced age and males with GU malignancies, especially prostate cancer with a history of radiation and urologic procedural interventions, were the most common risk factors. Pelvic and pubic discomfort was the most frequent clinical presentation with lack of systemic symptoms. MRI was the most common diagnostic mortality for early changes. In patients with risk factors who present with pelvic discomfort, an early MRI may aid in timely diagnosis. Time from last cancer treatment or radiation therapy to onset of PBO symptoms may also be on the order of years; thus, patient symptoms should not be discounted as unrelated to prior cancer treatment regardless of how much time has passed since last cancer-directed therapy.

Points to consider for future studies include accounting for the optimal timing of antibiotic therapy or debridement in PBO pathogenesis and providing antibiotics in cases where no fistula or abscess is present on imaging. It is possible that providing antibiotics without surgical intervention if PBO is detected early, before the progression of bony destruction, may provide better outcomes compared to antibiotic treatment alone when antibiotics are started at a later point in the illness. (Anele et al., 2022; Burriss and Abualruz, 2023; Smeyers et al., 2024; Walach et al., 2024).

The strengths of our case series include the fact that it is the largest retrospective cohort from a single center to date focusing on real-world outcomes in cancer patients, along with the extended duration of follow-up. The limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and lack of standardized treatment approach and baseline patient risks that preclude any meaningful comparisons between conservative and surgical treatment approaches.

In conclusion, the management of PBO should utilize a multi-disciplinary approach that includes the oncologist, orthopedic surgeon, interventional radiologist, infectious disease specialist, and rehabilitation specialist. Any pubic-bone-related discomfort in patients with a history of pelvic malignancy – even long after treatment completion – should be promptly investigated with an MRI for early signs of PBO. Antibiotic therapy should be based on bone aspirate cultures (ideally obtained off antibiotic therapy), even for cases where aggressive debridement may not be possible. A combination of surgical debridement plus targeted antibiotic therapy offered the best outcomes.

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

AML, MV, PAM, MK, and AK contributed to the study design and methodology. AML performed data collection, analysis, and visualization. BM performed data collection and visualization and drafted the tables. MK contributed to funding acquisition. AML and AK contributed to writing the original draft. All authors contributed to reading, revising, and approving the article.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

This case series was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center under protocol #19-478 “Umbrella Protocol for Evaluations of Infections in Solid Tumor Oncology Patients” and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki protocol.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank the Orthopaedic Surgery Service and Department of Medicine: Infectious Disease Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for their commitment to treating these patients.

This research has been supported by the MSK Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (grant no. P30 CA008748) at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. We acknowledge the Sheldon Rosenfeld Memorial Fund for their generous support of research by infectious disease fellows at Memorial Sloan Kettering.

This paper was edited by Alex Soriano Viladomiu and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ambrosini, F., Zegna, L., Testino, N., Vecchio, E., Mantica, G., Suardi, N., Zaramella, S., and Terrone, C.: Management of osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis following urinary fistula in patients with radiation-induced urethral strictures after prostate cancer treatment, Cent. Eur. J. Urol., 75, 284–289, https://doi.org/10.5173/ceju.2022.8, 2022.

Anele, U. A., Wood, H. M., and Angermeier, K. W.: Management of urosymphyseal fistula and pelvic osteomyelitis: a comprehensive institutional experience and improvements in pain control, Eur. Urol. Focus, 8, 1110–1116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2021.08.008, 2022.

Berbari, E. F., Kanj, S. S., Kowalski, T. J., Darouiche, R. O., Widmer, A. F., Schmitt, S. K., Hendershot, E. F., Holtom, P. D., Huddleston, P. M. 3rd, Petermann, G. W., and Osmon, D. R.: Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults, Clin. Infect. Dis., 61, e26–e46, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ482, 2015.

Burriss, N. and Abualruz, A. R.: Pubosymphyseal urinary fistula following radiation therapy of bladder sarcomatoid tumor, Cureus, 15, e46261, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.46261, 2023.

Chen, J., Black, N. R., Lindsey, R. W., and Hagedorn, J. C.: Serial surgical debridement and fixation of chronic pelvis instability secondary to pubic symphysis and sacroiliac osteomyelitis: a case report, J. Orthop. Case Rep., 11, 103–106, 2021.

Devlieger, B., Wagner, D., Hopf, J., and Rommens, P. M.: Surgical debridement of infected pubic symphysitis supports optimal outcome, Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg., 141, 1835–1843, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-020-03563-8, 2021.

Gupta, S., Zura, R. D., Hendershot, E. F., and Peterson, A. C.: Pubic symphysis osteomyelitis in the prostate cancer survivor: clinical presentation, evaluation, and management, Urology, 85, 684–690, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2014.11.020, 2015.

Hansen, R. L., Bue, M., Borgognoni, A. B., and Petersen, K. K.: Septic arthritis and osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis – a retrospective study of 26 patients, J. Bone Joint Infect., 7, 35–42, https://doi.org/10.5194/jbji-7-35-2022, 2022.

Hawkins, A. P., Sum, J. C., Kirages, D., Sigman, E., and Sahai-Srivastava, S.: Pelvic osteomyelitis presenting as groin and medial thigh pain: a resident's case problem, J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther., 45, https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2015.5546, 2015.

Lavien, G., Chery, G., Zaid, U. B., and Peterson, A. C.: Pubic bone resection provides objective pain control in the prostate cancer survivor with pubic bone osteomyelitis with an associated urinary tract to pubic symphysis fistula, Urology, 100, 234–239, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2016.08.035, 2017.

Nosé, B. D., Boysen, W. R., Kahokehr, A. A., Inouye, B. M., Eward, W. C., Hendershot, E. F., and Peterson, A. C.: Extirpative cultures reveal infectious pubic bone osteomyelitis in prostate cancer survivors with urinary-pubic symphysis fistulae (UPF), Urology, 142, 221–225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.095, 2020.

Peltola, H. and Pääkkönen, M.: Acute osteomyelitis in children, N. Engl. J. Med., 370, 352–360, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1213956, 2014.

Pham, D. V. and Scott, K. G.: Presentation of osteitis and osteomyelitis pubis as acute abdominal pain, Perm. J., 11, 65–68, https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/06-119, 2007.

Romanò, C. L., Logoluso, N., Elia, A., and Romanò, D.: Osteomyelitis in elderly patients, BMC Geriatr., 10, L15, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-10-S1-L15, 2010.

Ross, J. J. and Hu, L. T.: Septic arthritis of the pubic symphysis: review of 100 cases, Medicine (Baltimore), 82, 340–345, 2003.

Sambri, A., Spinnato, P., Tedeschi, S., Zamparini, E., Fiore, M., Zucchini, R., Giannini, C., Caldari, E., Crombé, A., Viale, P., and De Paolis, M.: Bone and joint infections: the role of imaging in tailoring diagnosis to improve patients' care, J. Pers. Med., 11, 1320, https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11121317, 2021.

Sexton, D. J., Heskestad, L., Lambeth, W. R., McCallum, R., Levin, L. S., and Corey, G. R.: Postoperative pubic osteomyelitis misdiagnosed as osteitis pubis: report of four cases and review, Clin. Infect. Dis., 17, 695–700, https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/17.4.695, 1993.

Shu, H. T., Elhessy, A. H., Conway, J. D., Burnett, A. L., and Shafiq, B.: Orthopedic management of pubic symphysis osteomyelitis: a case series, J. Bone Joint Infect., 6, 273–281, https://doi.org/10.5194/jbji-6-273-2021, 2021.

Smeyers, L., Borremans, J., Van der Aa, F., Herteleer, M., and Joniau, S.: The complex challenge of urosymphyseal fistula and pubic osteomyelitis in prostate cancer survivors, Eur. Urol. Open Sci., 70, 43–51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euros.2024.09.008, 2024.

Spellberg, B., Aggrey, G., Brennan, M. B., Footer, B., Forrest, G., Hamilton, F., Minejima, E., Moore, J., Ahn, J., Angarone, M., Centor, R. M., Cherabuddi, K., Curran, J., Davar, K., Davis, J., Dong, M. Q., Ghanem, B., Hutcheon, D., Jent, P., Kang, M., Lee, R., McDonald, E. G., Morris, A. M., Reece, R., Schwartz, I. S., So, M., Tong, S., Tucker, C., Wald-Dickler, N., Weinstein, E. J., Williams II, R., Yen, C., Zhou, S., and Lee, T. C.: Use of novel strategies to develop guidelines for management of pyogenic osteomyelitis in adults: a WikiGuidelines group consensus statement, JAMA Netw. Open, 5, e2211321, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.11321, 2022.

Upadhyayula, S.: Relapsed symptoms in a patient treated for pubic symphysis septic arthritis/adjacent osteomyelitis: diagnostic challenges, Case Rep. Infect. Dis., 2020, 8819268, https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8819268, 2020.

Walach, M. T., Tavakoli, A. A., Thater, G., Kriegmair, M. C., Michel, M. S., and Rassweiler-Seyfried, M. C.: Pubic bone osteomyelitis and fistulas after radiation therapy of the pelvic region: patient-reported outcomes and urological management of a rare but serious complication, World J. Urol., 42, 461, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-024-05155-2, 2024.

Wechsler, B., Devries, J., and Yim, D.: Pubic symphysis osteomyelitis with associated vesico-symphysis fistula: a difficult diagnosis, BMJ Case Rep., 14, e245034, https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2021-244336, 2021.